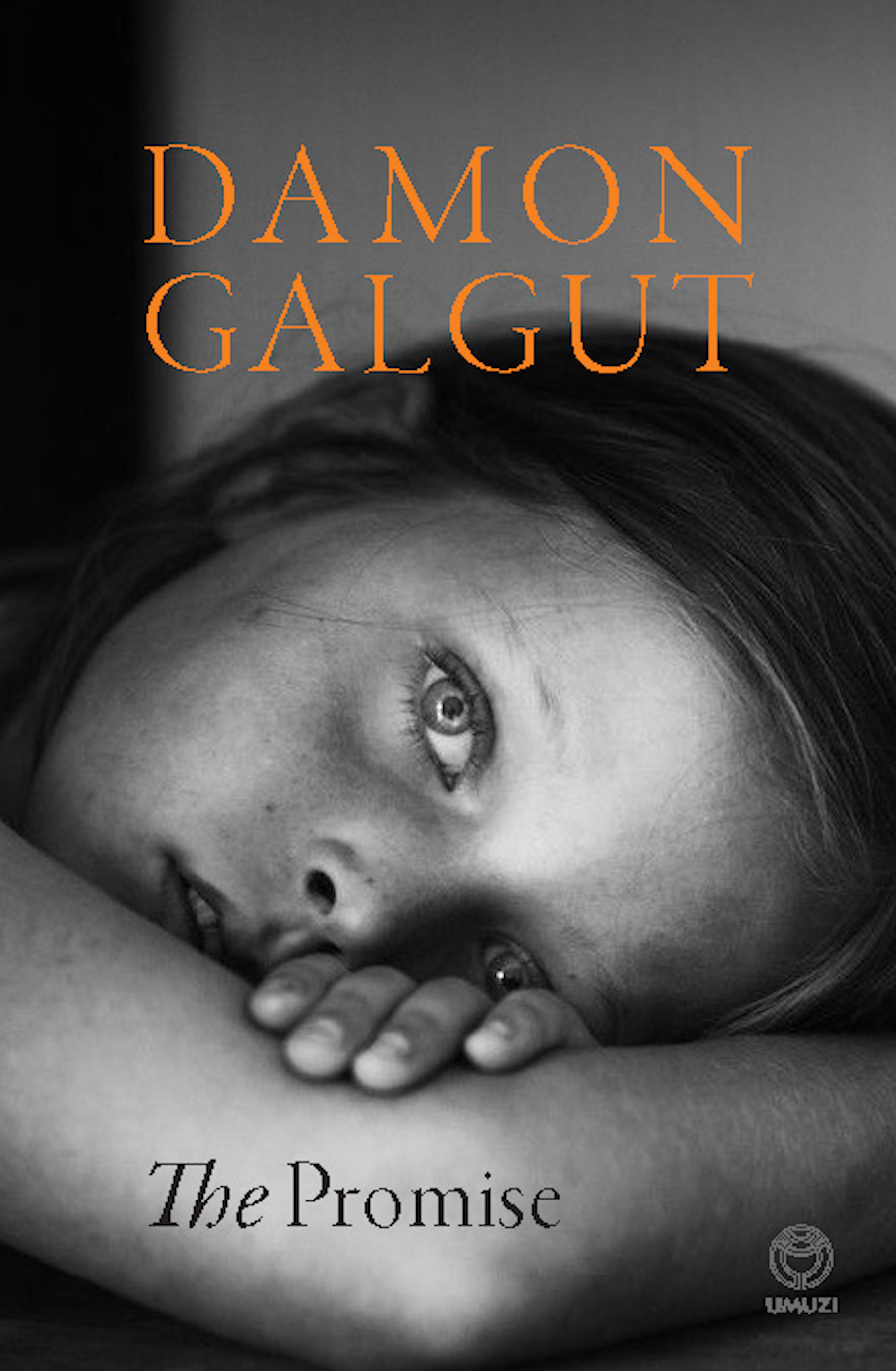

Time was the rare gift that celebrated director Sylvaine Strike was given with her latest production, The Promise, written and adapted (from his novel) by author Damon Galgut. She tells DIANE DE BEER more about the extraordinary process which started more than 18 months ago and is on at The Market (until November 5) following its recent Cape Town run:

“In a way, The Promise selected me,” she explains, because Damon approached her to adapt it for the stage, thinking that she would probably be the right fit because he had foreseen that it would have to be done very theatrically and very physically if it were to have a theatrical life at all.

She was utterly smitten by the idea, but insisted that Damon adapt it alongside her because she was reluctant to tinker with his text. “I needed him to travel the road and structure it in a way that he would feel could live as theatrical version.” She had read the novel twice even before he contacted her and was delighted.

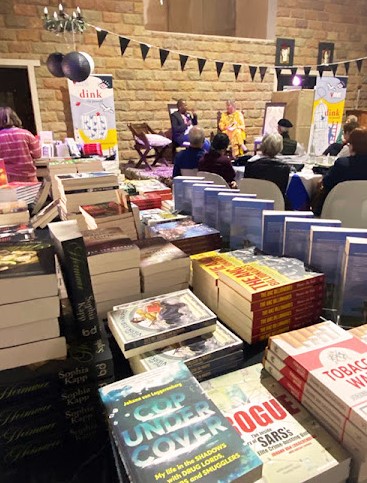

The Promise with the full cast as well as author, Damon Galgut (left) and Sylvaine Strike (right).

When it came to casting, it began with finding the right person to set the bar from a physical perspective and she knew from the outset when reading The Promise and imagining who her Anton could be, that it was Rob van Vuuren.

Gifted this opportunity of a role that is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, Rob was thrilled just to delve into this exquisite character and the very many facets of it. Sylvaine knew he would be the one who she would work off in finding the rest of the family, which includes Frank Opperman as Anton’s father, an Afrikaans patriarch, Kate Normington as his mother, jenny Stead as Astrid, his middle sister, and the young Jane de Wet as Amor

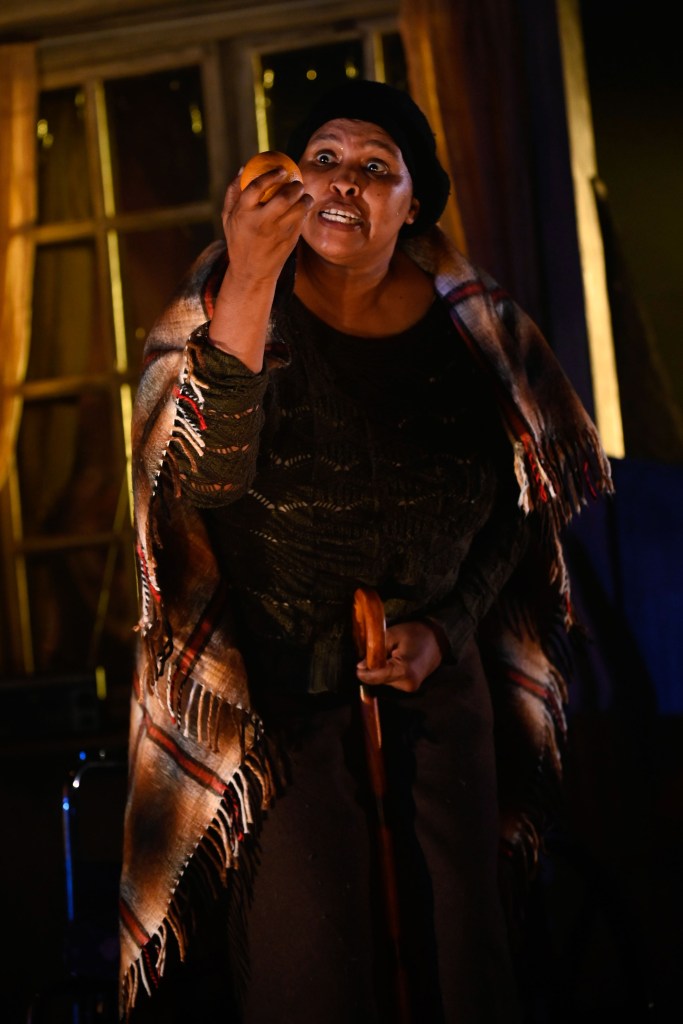

“The pivotal and most important character of Salome is played by Chuma Sepotela, who holds this exquisite part in two dimensions in the sense that she’s also the narrator of the piece, as Chuma herself, who plays the story conjuror.”

Sandu Shando plays Lukas, Salome’s son, and “the amazing Albert Pretorius and Cintaine Schutte, both adding deep dimension, comedy and pathos in the roles of Tannie Marina and Okkie as well as the many characters they portray,” she concludes.

In total it’s a cast of 9 and, before anything else, they did a workshop with Sylvaine to discover the physical language as the blueprint to the play.

In rehearsals: the cast and director Sylvaine Strike.

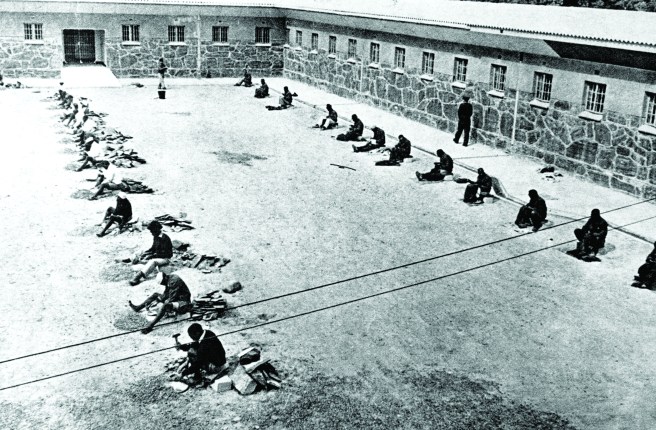

With both the director and writer growing up in Pretoria, their coming together was almost written in the stars. “I think growing up in Pretoria and being aware of the glaring chasm between the haves and the have nots, the ability for Pretoria to ride that knife edge between ignoring the political reality, the lies that have been woven to its children, the incredible duality between darkness and light, tragedy and comedy that this book engages with and its calling out for us to face the shame for how we lived,” all of that made the book irresistible.

“There’s no escape but to look it in the eye, which is what this was and showing what it felt like for me. The novel forced me to do it as it named everything I was feeling growing up there as a child and being a teenager there and sensing that something was so terribly wrong with it.

The full cast on stage. Photographer: Claude Barnardo.

“Four decades of Pretoria so distinctly captured, I rose to the challenge of telling the story on stage because I wanted to reach people with it and make them feel what it felt like for me to read it and everything it made me feel to confront our whiteness in its brutal hideousness and its complexity and own it.”

Once the decision was made, she and Damon sat for two solid weeks unpacking the novel. At first he really battled with seeing how it could be put on stage. Sylvaine thinks that in his mind the locations were so specific that it took some time for them to understand the kind of language it would need in order to tell the story.

“We both agreed that the very fluid narrative that Damon captures and writes in, a narrative that changes perspective all the time, changes its mind all the time, needed to come from a chorus almost in the Greek tragedy sense, to comment on the action, to speak to the hero or the anti-hero, to contain their thoughts, and to move swiftly through the action alongside it.”

Scenes on stage. (Pictures: Claude Barnardo)

Neither the reader nor the writer could hold on to all their darlings. They knew they had to lose certain bits of the novel, cutting and culling, choosing only the very essential parts of the story, and look at compressing it into a time frame that would suit theatre, so much more condensed than in a book.

They also needed to find a theatrical language and a physical language that was able to edit between time and place very swiftly, where actors could age from one decade to the next simply by using their bodies. Damon then proceeded to write five drafts which incorporated this language and refined it more and more and more.

In between the first and second draft they had a workshop which Damon attended in which she worked with her cast and at which Charl-Johan Lingenfelder (music/soundscape) and Joshua Lindberg (set and lighting design ) as well as Penny Simpson (costumes) were present. “It was a collaborate effort to reach a place where script was done and created,” she explains.

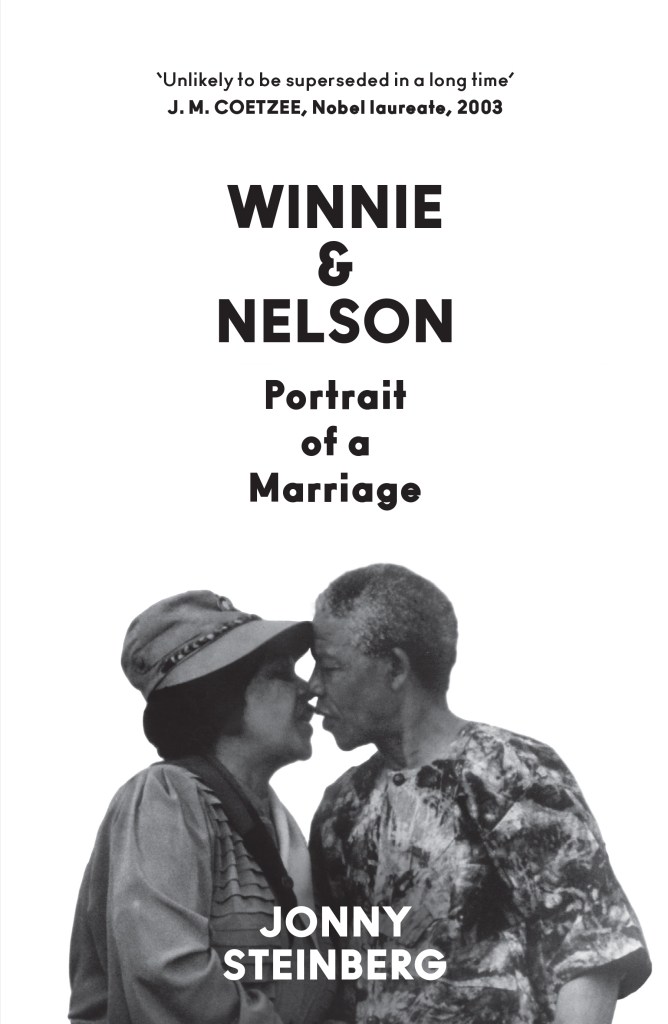

Wearing her heart on her sleeve, director Sylvaine Strike.

Photographer: Martin Kluge

In conclusion, after all the hard work, the introspection, a fantastic cast, long hours and hard work, she hopes audiences take a good hard look at our country – and a soft look as well. “And by that I mean allowing us to enter its deep humanity and inhumanity, looking into a mirror, admitting our own whiteness, hearing it, not making excuses for it, not trying to explain it, but most of all really looking at the relationship we have as South Africans with each other.

“There’s also the microcosm of a family and its domestic worker Salome, which is a microcosm for the dynamics within our country, the difficulties, the obstacles, the promises made and broken, the lack of care we have for one another, the care in some aspects, about our country looking at itself, not being spoken down to, but simply observing itself, taking a step back to see more clearly, not back in time, just to get more focus on where we’re at.

“And what I love about The Promise is that it doesn’t offer any solutions, just gives us a glimpse of what we have done and what we have become over the last four decades of our country’s democracy.”