Daniel Geddes Pictures: Odette Putzier

After much acclaim, following it’s London debut with Jack Holden, and then a Joburg run starring local actor Daniel Geddes, Cruise, heads for Cape Town for a short season (April 12 to 30) at the Homecoming Centre (formerly The Fugard Theatre). DIANE DE BEER chatted to the British playwright/actor about the play and the handing over of this his first stage-produced play, which he had both written and starred in back home:

It was as if all the stars aligned for actor/playwright Jack Holden with the creative processes surrounding his first play Cruise, which is having its second local run in Cape Town this month.

“I had the idea of the show for a while, for many years actually. It was based on a phone call I heard while I was volunteering for Switchboard, an LGB+ helpline here in the UK. I took that call in 2013.

“The story struck me as so moving and powerful and life-affirming that I knew I needed to tell it someday, somehow, and it was only in the pandemic when I was locked down at home with nothing else to do, I finally got on and did it. So in that sense it saved me because it really gave me a focus during the first lockdown here,” he explained.

But the writing only started in 2020. He thinks that it might have had something to do with the context of sitting with another epidemic, Covid, that made him reflect upon the sort of fear and terror that the gay community must have gone through in the UK especially, with the 1980’s HIV and AIDS. (It was more widespread in South Africa, affecting more communities).

A lot of the research about Soho where the play is set was quite easy to do online. But, he explains, “the stuff that gave the show the texture that I think makes it sing, are the interviews I did with some older gay friends that I’m lucky to have. I asked them about their time in Soho in the 1980s. Neither of them claimed to be seen kids, but they had memories which were incredibly useful, and gave so much texture to the piece. “

Initially he thought it might be a short film, but then he thought, no, be ambitious. “I also predicted that when theatres reopen after the pandemic, they are probably not going to put on massive shows, so if I can make it a solo show, that would be great. I’d performed a few monologues of other people’s writing previously in my career, so I knew I could do it and I wanted to do a show with John Patrick Elliott doing the music again.”

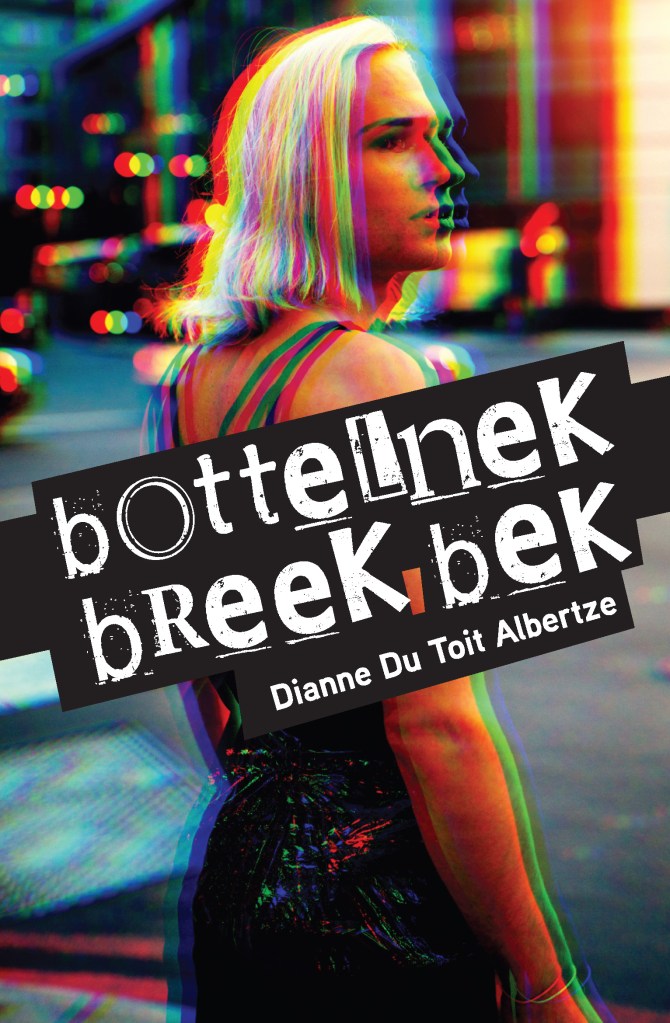

Daniel Geddes in Cruise.

They had worked together before and again with great foresight, Jack’s thinking was about producing a show that would land with a huge bang.

“I have a very strange relationship with the pandemic. At the start of the pandemic, I thought my career was over and at the end of it, my career was better than it had ever been, so it was a weird time.”

Theirs was the first play to open in the West End and the first new play as well. “I think people were so hungry for the live experience and Cruise is loud and brash and all of those things. I think because it’s such an ultra-high-octane live experience, people were so receptive to it, so emotional behind their medical masks, that it landed well,” which was also the intent.

From the start, the writing of it, once he got in a room with John, was actually very quick, because it was always going to be only one actor (Jack) with the DJ (John), which meant he would be playing all the parts, which also provided certain limitations. They knew it would be roughly 90 minutes straight through and he wanted it to be an odyssey that bounces around all the bars and clubs and pubs of Soho. “It’s quite a classic hero’s journey that he had to go on,” he says.

Primarily he was trying to create something that would entertain people and he doesn’t think entertainment has to be light all the time. In fact, he argues that entertainment is better if there’s a bit of darkness, a bit of sadness mixed in there, a bit of humanity that lifts the lightness and makes it even more delicious.

“I was hoping to entertain people and as I was taking on the subject of HIV and AIDS in the 1980’s, I obviously wanted the piece to feel authentic. And that was the scariest thing which only surfaced when I got to performances. I suddenly thought this could be high risk, I could have judged this wrong.”

But he had gone about the whole process in a very thoughtful way. His research was thorough and he talked to the right people with good people surrounding him who told him if something wasn’t ringing true. “And indeed, in rehearsals we had several changes and bits to cut.”

He also wanted to dive into the music of the era which hugely adds to the entertainment element of the piece. “I love ’80s music. It can be really, really good and it can also be really, really bad and I wanted to play with that. There’s been a real moment of ‘80s nostalgia, so I thought it would do really well.

“I wanted the music to be in the DNA of the play and that‘s why I worked so closely with John. I brought a few pages of text to our first workshop and he brought samples of ‘80s music. And we started mixing it together. That means the show has musicality in its veins. I love traditional shows and when it works it absolutely blows me away, but there’s no shame in putting on a show and entertaining people.

“We have so many tools at our disposal in theatre; sound, light, music, smoke, movement. And especially with a solo show, you don’t have to use all of those, but I really wanted to. I never dared to hope that the show would get as big as it did.”

Because he is dealing with something in the past, yet in a strange way linked to our present circumstances, the content has huge impact. It’s obviously been written with performance and watchability in mind. Jack has a great way with words with the text written as a kind of rhythmic monologue interspersed with music, which also passes on the message. It holds your attention throughout.

And then there’s Daniel and the local production. Jack was surprised that South Africa was the first outside of the UK to stage Cruise, “but I was also cheered by it and love it. Obviously South Africa’s history with HIV and AIDS is well known, so on that front it struck me as completely logical.

“I loved watching the South African production. It was surreal watching someone else performing Jack (me) performing the show. It was quite a mind-bending experience and really informative to see how the show can be interpreted in different ways.

“And yes, humbling. It’s not just me who can do this, other actors can do this, so I’m really thrilled that it’s getting another life. I’m so pleased about the Cape Town run, because they really deserve another go at it,” he concludes.